|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SUMMARY

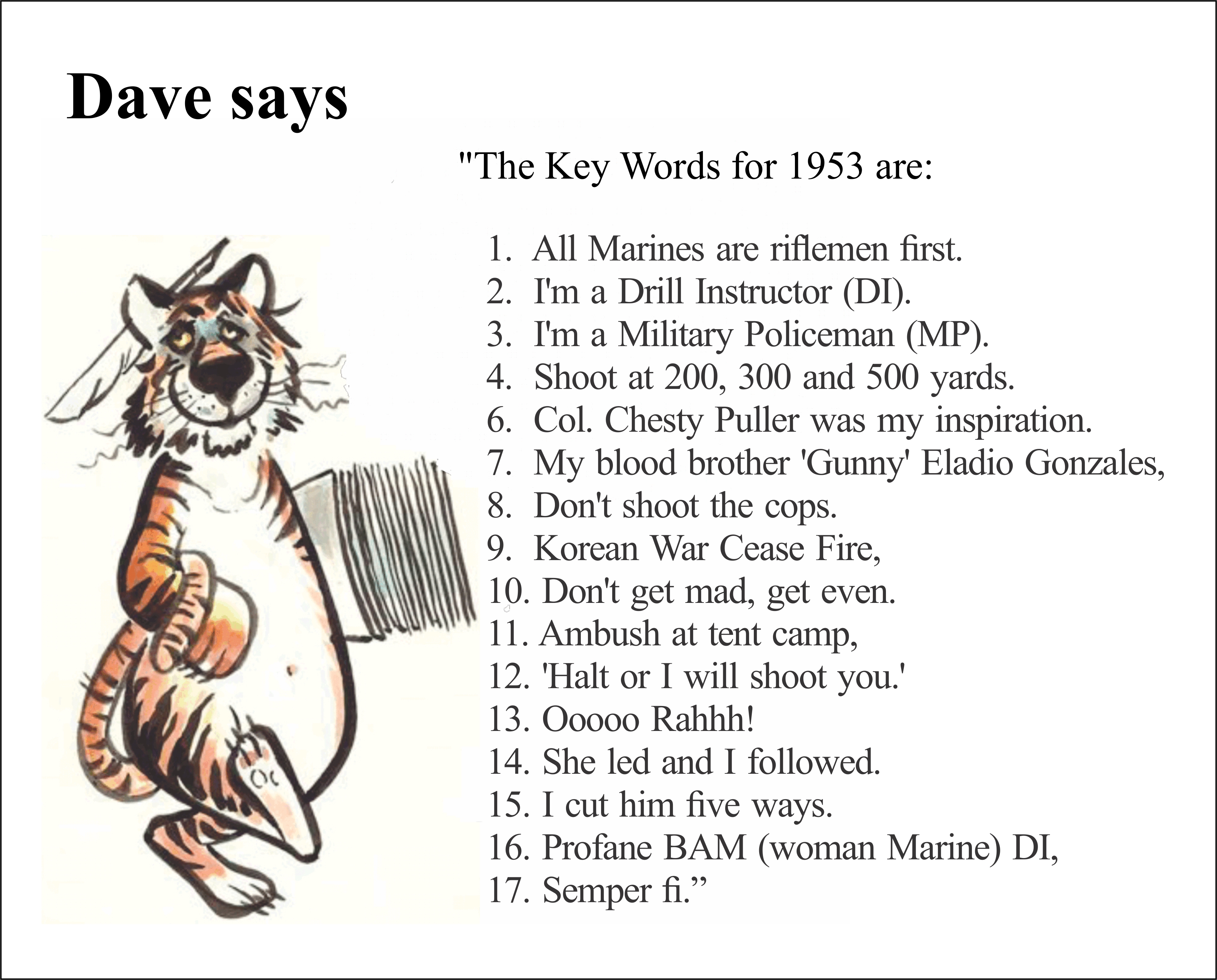

I actually enjoyed Boot Camp at the U.S. Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego, California in the spring of 1953. The Marines loaned me the best rifle that I had ever fired, free ammunition, and let me shoot it for weeks at a time at the Camp Mathews rifle range. They also gave me three nutritious meals every day; some of which were fairly decent if you are not too picky or have a lot of condiments. They also gave me the opportunity to earn one of the most respected military uniforms on God's green earth. Who would not be proud to wear U.S. Marine "dress blues, spit shined shoes and a light coat of oil?" You talk about a chic magnet; sometimes that seemed to be what our Recruit Platoon 118 was all about.

With all of the calisthenics and other physical and mental exercises all day every day, I was in the best physical shape of my life. That included when I was playing first string offensive/defensive end, punting, kicking field goals and extra points for the junior college champion El Dorado Grizzlies, as well as playing sem-professional baseball and pulling pipe in the Oil Patch during the sweltering Kansas summers. A second semester sophomore when I enlisted, I gave up a full football scholarship at Kansas State University for my junior and senior years, as well as a minor league contract with the Boston Red Sox. Somehow, I actually believed that I could easily get all of that good stuff back again even after a three-year absence in the Marines. Silly me. While still in boot camp, some overly enthusiastic optimist in the chain of command thought that I could become a decent infantry officer, so they sent me to Drill Instructors' School as the first step in transitioning from enlisted to officer status while most of my platoon went to Korea to get even with the North Korean and Chinese communist hoards, which was the primary reason that I joined the Marines. Until that time, an applicant for DI School had to be at least a corporal (I was only a Pfc.), have an officer's IQ (120 points or more), and preferably have combat experience. One out of three did not seem like a promising average to start down that road. At that time, DI School was one of the most difficult and demanding schools in the Marine Corps. On average, about 50 percent of the qualified Marine applicants who were accepted by DI School either flunked out because of the constant written and pop tests every day, or the constant physical exercising and drilling on the parade grounds. Except for the IQ requirement, I was definitely over my head and I knew it. So I did not take liberty breaks off the base, memorized the large and very precise Landing Party Manual about all things Marine, and survived the many challenges to become one of only three graduates in my class who were immediately assigned to a recruit platoon although the ranking Gunnery Sergeant hated my guts because he thought I was laughing all the time. Actually, when physically overexerted, I sounded like I was laughing every time I sucked air during extensive exercises when other guys were tossing their cookies and dropping out of the program. Well heck, you can't please everybody every time. As the junior DI with Platoon 205, I worked hard to teach our 75 recruits how to do the "five S's" between reveille and breakfast formation; march and run double time together in many formations; spit shine their shoes until they gleamed; iron military creases into their Class "A" shirts (i.e., blouses) and trousers; hike 20 miles into the southern California mountains with just one canteen of water each; shoot our enemies at 200, 300, and 500 yard ranges; skewer those same enemies on the pointy ends of our bayonets if they are dumb enough to get that close; and write a letter home to Mom and Pop at least every Sunday afternoon. About that time, iconic Marine Colonel, later Major General, Lewis "Chesty" Puller said that too many of his close air support pilots had not been as aggressive as he wanted during the "Frozen Chosin Reservoir" Campaign in the mountains of northern Korea. Chesty wanted some hard-charging enlisted Marine grunts to become pilots and show those Ivy League fraternity pilots how close air support should be flown. As a result, 12 enlisted Marines were chosen out of the 194,000 enlisted Marines in the Corps at that time. For some unforeseen reason, I was one of that dozen. No one was more surprised than me. In late September, I was transferred to Naval Air Station Moffett Field near San Jose, California to play football and basketball for the Red Raiders, work as a Military Policeman (MP) on patrol, and a Marine Guard at the super-secret Ames Laboratory where I was cleared for Secret although somehow I did not know about that while waiting for my summons to Pensacola, Florida for pilot training. We played the Armed Forces Football Game for 1953 on national TV. Our team lost because our best and only decent running back broke his leg during war-game maneuvers a few days before the game. With Marines, preparing for war always comes first. However, I did rather well because the TV announcer liked my punting and he said so repeatedly throughout the game. As a result, over the next few months I received ten full football scholarships in the mail from Kansas, Nebraska, Missouri, Colorado, Oklahoma State (A&M) and five other major universities. Of course, I chose the wrong school, but that's another story for another time. The best part about Moffett Field was finally receiving my Advanced Combat Training with elements of the famous 5th Marine Brigade of the 1st Marine Division that mauled the three Chinese Divisions assigned to destroy the 1st Marine Division during the "Frozen Chosin Reservoir" Campaign in North Korea during the winter of 1950/1951. Ooooo-raaah! I loved every minute of training in the mountains of northern California and could not have had better teachers or better examples than the veterans of the 5th Marine Brigade. SAMPLE SEA STORY

Floyd Snow's Roving Eyes

When we were temporarily billeted in the receiving barracks during our first two days as Marine recruits, the Drill Instructors (DIs) in charge of that barracks did their best (or worst) to change our cheap civilian crap ways. The first thing they did was line us up indoors in three squads at attention, and told us to find a spot on the bulkhead (i.e., the wall) straight ahead, lock our eyes onto that spot and keep them that way. Then they began their loud, profane orientation tirades, which distracted recruit Private (Pvt,) Floyd Snow (my good buddy who was later killed at the Pickle Meadow winter training camp after his one-year tour of duty in Korea) to move his eyes off his chosen spot on the bulkhead.

That was a heck of a "No No." So the DI grabbed this very large Indian guy and threw him against the bulkhead. However, although I was a "good guy" recruit and had not moved my eyes off my chosen spot on the bulkhead, I made the mistake of standing between Floyd and the bulkhead. I paid for that mistake as I was slammed against that bulkhead three times by Floyd's big body each time Floyd lost track of his spot on the bulkhead. Long story short, I was pretty well pounded to a pulp. However, Floyd was doing just fine as I absorbed his every impact meant for that darned bulkhead. In fact, that rascal was enjoying the excitement while I was paying the price for his darned entertainment. That's how I learned that come rain, flood, poop or blood, ol' Floyd could resist just about anything except temptation; just like me. SAMPLE SEA STORY

Gunny "Snake" Wanted Me Gone

Gunnery Sgt. (I forgot his name after so many years) was also a highly decorated veteran from WWII and Korea. He was a squared-away Marine, knew his business like the pro he was, and he looked like a poster Marine; that is, he did until he spoke. On line in combat for something like 18 months in Korea with Colonel Chesty Puller and the 1st Marine Brigade of the "Fighting First" Division, he must have suffered from battle fatigue, shell shock or something nasty like that because when he spoke, he would involuntarily shoot the tip of his tongue out between his lips and then snap it back into his mouth like a snake. From my first day in DI school, Gunny Sgt. Snake did not like me one little bit, but I don't blame him. First and foremost, I was not qualified according to the old rules. Maybe it was also because he thought that I laughed a lot during calisthenics while others were sucking air and/or dropping out, especially when only mad dogs and Irishmen should go out in the noonday sun. What Gunny did not know was that when pushed to my physical limits, I grunt a lot and make a chuckling sound rather than whine while sucking air. But what the heck, I had quite an advantage. I was a two-year college football letterman who had just graduated from 12 weeks of physically challenging boot camp. Many of my new classmates were wounded Korean War vets who were recently released from various hospitals to return to active duty but were not quite up to the rigors of continuous mental stress as well as the physical challenges and calisthenics of DI School. Each of those Marine warriors wanted to be a DI, and each of them had definitely earned the right to try. Maybe Gunny Snake thought that a candidate who was grinning and chuckling a lot on the side was a dummy and did not belong in his prestigious DI school. Or more than likely, he may have heard that I secretly called him Gunny Sgt. Snake, and he was not pleased. I do not know his exact motive, but every day and in every way, he was determined to kick my donkey out of his school. He certainly had a big advantage, and I was definitely the underdog in that contest. That was fuzzy bug time. Like they say back in Kansas: "When all has turned to clabber, eat a fuzzy bug the first thing in the morning, and your day just has to get better." SAMPLE SEA STORY

FORM FOR SHELTER HALVES

As I said before, all Marines take a 30-inch step at 90 steps per minute when marching in formation to get from point "A" to point "B." No more, no less, no latitude. The stride and steps per minute are exact. There is no room for deviation. "One heel, one heel" the DI chants as up to 75 boot heels hit the ground simultaneously as one. If you have ever heard that sound, you will never forget it. The well-trained, highly experienced DI turns the cadence and commands into something like a gruff song so that the cadence is always precisely the same, even many years later. However, most music majors need not apply.

The most difficult, arcane formation on any parade ground was "Form For Shelter Halves" which had something like two dozen individual commands to open the platoon side to side, then front to rear as I remember, but don't hold me to the 24 commands after more than 60 years. The M1 rifles were stacked upright in groups of three, the field marching packs were removed, the canvas-like shelter halves (each was one half of a pup tent) were removed, the tents on their folded poles were erected, the tent pegs were not driven in the ground except on dirt drill fields, and then each two Marines stood at parade rest at each side of the open flap end of the laid-out pup tent. Each command was sharp and clear, and the final formation had to be precisely aligned from front-to-rear and side-to-side. Except for a few Old Corps DI's (from the "wooden ships and iron men" era), to my knowledge no one after WWII ever performed that maneuver except maybe for beer bets in enlisted men's slop chutes (i.e., beer bars). In fact, most Marines in 1953 had never heard that series of commands. And don't bother looking for it in the current "Landing Party Manual" because it went out after Korea when Marines in the field no longer carried those shelter halves around. Reading the tea leaves, I was absolutely sure that was the series of commands with which Gunny Sgt. Snake would ambush me on the last day and the last test in DI school. Somehow, I just knew it. So I studied it for more than three weeks; day and night whenever I had a spare minute or more. I broke it into four distinct series and extended the preparatory commands in a verbal two-count hesitation before each barked command of execution. When I finally had it down pat, I told nearly every guy in our class that Gunny Snake would try to fail me on the last day with the "Form For Shelter Halves" series of commands, so that each candidate would be sure to bring all of the prerequisite equipment in their field marching packs and be ready to perform at a rapid, uninterrupted tempo. I even had a few dry runs with the guys in my squad at the far other end of parade grounds (huge asphalt drill field) and behind the base movie theater where no instructor from the DI School was likely to see us practicing those maneuvers over and over again. Finally, DI Class 19 of 1953 fell out on the parade grounds (sometimes called the "grinder") where Gunny Snake called each DI candidate front and center, and announced the random marching maneuver to be performed. Since we had an unusually large class for this last stage of training, most candidates had very abbreviated appearances; something like: "Atten...hutt. Left...face. Forward...march. To the rear...march. To the rear...march. Platoon...halt. Right...face. Parade...rest." And then another candidate would be called front and center, and we would go through another brief routine. That rain dance went on for well over an hour. Although I was the Squad Leader for the First Squad, I was not called front and center until the last man to qualify. With a dead-pan lack of expression, Gunny Snake announced my qualifying drill field maneuver: "Form For Shelter Halves." "Aye aye, Sir. Atten...hutt. Dress right...dress." Then I took that whole platoon through the entire maneuver in cadence, and by the numbers as smooth as a black cat's fanny. Then I reversed the order and put them back into a platoon formation by the numbers in a little over a minute while Gunny Snake's mouth actually fell open as he watched in utter amazement as every man in the platoon bit his tongue or inner cheek and tried very hard not to laugh out loud. As I returned platoon command to Gunny Snake, over his sagging shoulder and about 50 yards beyond, I could see MSgt. Ramsey standing in the shade of the Administration Building as he watched the whole performance...with approval? The next day when I received my orders right after our graduation ceremony and class photograph, I was one of only three newly minted DIs who were immediately assigned to various recruit platoons as working DIs. All of the remainder of the graduates were assigned to a DI pool on the base, or were sent to Camp Mathews as rifle coaches. Thank you, Sun Tzu, you murderous old Mongolian motivator, you. I read your book. SAMPLE SEA STORY

Cpl. Hooker Cpl. Hooker was a Marine's Marine. At least five veterans of the 5th Marines each told me how Cpl. Hooker found himself masked from the battle by a terrain anomaly as seemingly all of the Chinese grunts in Korea were advancing across a valley toward his position on a hill. So while his buddies poured fire at the Chinese from within their bunkers or their sandbagged fighting holes, Cpl. Hooker stood up in his fighting hole so he could see better, and calmly fired round after round of aimed fire into the onrushing Chinese hordes. What a guy! His buddies in Korea also told me that Cpl. Hooker was afraid of frogs. When I doubted that, they told me to go ask him if I did not believe them. So I did. In response Hooker said: "Yeah, heck yes; I'm afraid of frogs." I asked him why, adding a flippant: "Heck, they can't bite you, can they?" Hooker looked at me like I was a slow learner and replied: "They have a mouth, don't they? SAMPLE SEA STORY

"Oh Yes You Will" One afternoon, the fire alarm went off in the Marine barracks and interrupted several payday poker games scattered around the barracks. Already in our dungarees, about a dozen of us in the area dropped everything, grabbed our rifles, helmets and 782 web gear, and ran to the Corporal of the Guard post in the basement near the brig. There we learned that the fire was burning out of control on both the 1st and 2nd decks at the other end of the same red brick, U-shaped building where we were billeted. So we took a shortcut through the building and got to the fire way ahead of the Navy Crash Crews/Firemen who had been working at the other end of our 2½ mile long duty runway and were just starting on their way back. I believe that we could hear them coming, but they still had a long way to go. As the other Marines spread out to handle security and crowd control, the Officer of the Day (OD), MSgt. O'Day, ordered me and another Marine into the burning building to make sure that everyone had been evacuated. I took the second deck and my buddy took the first deck. "Have no fear, the Marines are here." The fire on the second floor was a roaring, blazing inferno with heavy black smoke in the barracks area of the Navy Casual Company, so there was not much I could do there except yell a lot and stay low. However, I heard no response and that area was getting awfully unlivable with unknown things popping, sizzling and exploding all over the place so I moved on ahead of the expanding blaze. Anything in that fire was toast. As I was kind of duck waking low to stay under the swirling black, choking smoke, I heard a couple of guys singing loud and proud in the showers as if nothing was wrong. Apparently those guys were using very hot water so that the effects of the turbulent steam in there were still strong enough to somewhat block the smoke from burbling into their shower area. All hell was breaking loose outside of the shower room, but those two sailors did not have a clue that the building was burning down around them. They were singing so loud and were covered with soap and shampoo when I got right up to them in their showers before they knew that I was in the room with them. Obviously, we had to get the heck out of there darned quick or we would be cut off at the one door exit. However, there was another problem. Get this; we were squatting down in the hall to stay below the thick black smoke, and the roar of the fire and things breaking and exploding in the heat were getting too darned close for comfort. However, both of those guys wanted to go back to their blazing quarters to get their clothes. I could not believe it, so I had to get in their faces and use my old DI voice and vocabulary to convince them that everything back there was burning like the four corners of hell, and if we did not get the heck out of there very quickly, we would be burning too. That was not an exaggeration. I could not understand why they could not understand the danger we were in at that time. All these two sailors had to wear were two fairly small, government issued towels, flip flop sandals, and nothing else. Then, when they looked out a second-story window at the gathering crowd below, many of whom were Waves(i.e. women sailors), both sailors stubbornly insisted that they were not going to go out there like that, as if they had any other choice. They did not, so I put my bayonet on the business end of my M1 rifle and assured them that yeah, we would do that very thing, and we would do it eee-mediately if not sooner. I was not about to fry just because they were about to die. So I herded those two very reluctant sailors down the stairs under protest. We stopped at the outside door where both of them looked out and repeated that they were not going out there as the fast-moving fire seemed to half way surround us. That's when I reverted to Marine Drill Instructor one more time and literally muscled them out the door with my rifle just before the base firemen came running in with their hoses and knocking down everything that was not a permanent structure. I had to jump back to avoid getting a fire hose stuffed in my face. I was putting my bayonet back in my scabbard when our C.O., a full bull colonel and another veteran of the 5th Marine Brigade, walked up, shook my hand and assured me that I had just earned a Navy/Marine Letter of Commendation. For crap sakes, minus the Combat "V," that's what my blood brother "Permanent Pfc." Eladio Gonzales earned for saving the lives of his recon patrol during a deadly fire fight with the bad guys in Korea. That's just pure crazy. Hell's bells, all I expected was an "Atta' Boy" and a couple of cold beers from those two sailors at the enlisted slop chute some night around payday. |

|

Paper copies of 1953, Making a Marine Grunt Warrior can be purchased at Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, and local book stores. Ebooks can be purchased at www.Kobo.com and www.Amazon.com |